Tambo Grande’s 217th anniversary begins happily enough: a few residents gather for a candle-lit ceremony in the Peruvian town’s dusty Plaza de Armas. A brass band procession carrying an image of Jesus Christ pours from San Andres church, swelling the plaza crowd to more than 200. Children perform traditional dances. Fireworks explode.

Then someone lights a bonfire in front of the mayor’s office, and the anti-Canadian speeches begin. A teenage girl reads a poem on the ills of mining. The townsfolk responds to each point with fists raised and angry chants of: “Agro si! Mina no!” The finale is a pantomime featuring a man in “Canadian” drag–blond wig and floral dress–being unceremoniously banished from the village.

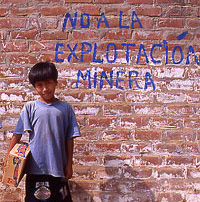

The next morning, geologist Andy Carstensen beams and waves to the locals enthusiastically as he drives through town. The geologist doesn’t seem to notice that his friendly waves are sometimes returned with backhanded gestures. He doesn’t acknowledge the graffiti: “No a la explotacion minera,” painted crudely on dozens of mud brick walls. Nor does he see the bonfire ashes still swirling in the plaza, remnants of the demonstration aimed squarely at Manhattan Minerals, the Canadian junior exploration company for which he works.

Carstensen’s enthusiasm is understandably resilient. After all, he’s sitting on the discovery of a lifetime here in northern Peru.

Barely 15 metres beneath Tambo Grande’s dusty streets, Carstensen’s drilling team has discovered a layer of barite holding an estimated one million ounces of gold. Deeper still are sulphides: 64 million tonnes of rock rich in copper, zinc and silver. The company has yet to determine the full cost of extraction, but in the ground, these two deposits are worth more than $2 billion at projected long-term mineral prices. And a year of test drilling in the surrounding desert has yielded signs that Manhattan Minerals is on the verge of hitting the big time.

“This is a dream come true for any exploration geologist” says Carstensen, Manhattan’s exploration manager. “Rarely will anybody ever make a new discovery in their career. Well, we’ve made four major discoveries in a year and a half. And there will be more to come. This is evolving into one of the largest massive sulphide deposits anywhere in the world.”

Analysts agree the junior exploration company may have come across what could be a world-class mining region in northern Peru. But the problem in Tambo Grande is people, not rocks. Developing TG-1, the jewel in Manhattan’s emerging mineral crown, means digging a pit where now sits this town of 16,000 people. Tambo Grande is also the social and administrative heart of a rich agricultural valley.

GUERILLA LEGACY

Anti-mining sentiments have been simmering in Tambo Grande since French geologists arrived with their rigs in the 1970s. At that time, Shining Path guerrillas controlled much of Peru. The French, says Carstensen, were pretty much run out of town.

The guerillas are gone now. But from the day Manhattan contractors hauled their own test drill rigs into Tambo Grande in mid-1999, the company has encountered deep mistrust and violent opposition. One attack on Manhattan’s compound resulted in US$1 million in damages to trucks and other gear. Dozens of locals–including a former mayor–have been charged with violence and mischief. Thousands of people have taken to the streets in anti-mining demonstrations. One 1999 protest paralyzed the town and nearby highways. And when Peru’s Minister of Energy and Mines flew in to talk about the project, he was stoned by a crowd of 200 angry villagers. All this, before the company has finished exploration work.

The conflict stems as much from the complexities of Peruvian village politics as the fears of a people all-too-familiar with their own country’s disgraceful environmental record. The irony is that the Canadian mining community–Manhattan included–is intent on setting an example of transparency, environmental stewardship and community development in Latin America.

Beginning in 1992, Peru liberalized investment rules and privatized state-owned mining interests. President Alberto Fujimori introduced safeguards for foreign investors guaranteeing 100 percent repatriation of profits, capital and royalties. The registration system for accessing mining concessions was streamlined. A series of acts strengthened environmental regulation, requiring mines to conduct environmental impact assessments (EIAs) and mitigate social and environmental effects.

Canadians, stymied at home by regulation and development costs, were quick to take advantage of the new, level playing field in Peru. By 1998, Canada was the Peruvian industry’s third most important source of investment capital. Barrick, Cominco, Noranda, and Placer Dome were among Canadian players with planned investments totaling more than $3 billion. Canadians are now behind more than 50% of mineral exploration ventures in Peru. Most of those ventures are led by juniors like Manhattan.

Under its 1999 agreement with the Peruvian government, Manhattan has until June 2002 to complete a feasibility study and environmental impact assessment (EIA) in order to earn its 75% share of the Tambo Grande concession. In a bid to ensure the company has the wherewithal to pull off the Tambo Grande project, the government also stipulated that Manhattan must operate another 10,000-tonne-per-day mine somewhere in the world and possess net assets in excess of US$100 million. Those latter conditions, combined with projected development costs of US$270 million, mean the junior will need to strike an association with a mining major or romance strong financial partners. For either option, it needs peace in Tambo Grande.

“A lot of people are watching what’s going on. If the mine wins acceptance, other companies will come running to work with Manhattan,” says Ian Thompson, the consultant Manhattan hired last May to make peace with local NGOs. Thompson has a reputation as a straight-talking troubleshooter for mining projects experiencing social conflict in Latin America. “This is emerging as a test study for mining in the region, especially the process by which people decide whether they want a mine or not. Twenty years ago, companies just showed up with a government order and told the people to pack up and leave. The government had near-absolute power.

“It is still possible to get permits for a mine virtually without consulting with local people,” Thompson adds. “But the Canadians know this isn’t socially acceptable. They would have every NGO in the world, not to mention shareholders–on their backs.”

Manhattan still has the right to appropriate land for which it has mineral concessions. But the politics of mineral exploitation have changed in Peru, Thompson says. “Now it’s a process of negotiation. Manhattan has adopted World Bank standards for consultation, but the inevitable consequence of that is you have to deal with all the social and environmental issues in a very public way.”

That creates a new set of challenges for Manhattan, not least of which is figuring out which organization it should be negotiating with. The company has met with village committees, five NGOs, the Catholic Church, a smattering of newly formed defense fronts and the mayor of Tambo Grande municipality. Local politics aren’t simple. Mayor Alfredo Rengifo Navarrete, who ostensibly represents some 70,000 people in the valley, gave Manhattan permission to drill in 1999, but now faces a move by anti-mining forces to oust him. The mayor’s enemies, furious that he had opened the door to Manhattan in the first place, have organized alliances of their own.

After months of factional infighting, those groups unified under the Front for the Defense of San Lorenzo and Tambo Grande. Manhattan signed a deal recognizing the Front’s place at the bargaining table in 1999–not that the Front is interested in negotiating.

“The people don’t want to talk anymore,” says Front leader Francisco Ojeda Riofrio. “We have agriculture here, and we don’t want to change it for mining.” Ojeda is a soft-spoken, dead serious schoolteacher who keeps a small farm in San Lorenzo, the irrigated valley north of Tambo Grande. Ojeda says his group has gained widespread support because Manhattan simply hasn’t made the effort to talk to people about their work. And, he adds, Peruvians have yet to see any benevolent examples of mining. “In Peru, mines have never brought development. They have always brought poverty, hunger, misery and destruction.”

DISASTER SCENARIOS

Peru has a well-documented history of mining’s power to devastate communities, denude hillsides and scour rivers with acid runoff, mostly around the Andean mining centre of Cerro de Pasco. The Front has gained core support from farmers who feel agriculture and mining simply can’t coexist. It’s a key point, because right now Tambo Grande has been completely dependent on farming since the San Lorenzo Valley was transformed from desert into a productive Eden by an irrigation project funded by the Inter-American Development Bank in the 1950s. The valley now supports a US$136 million fruit growing industry and is Peru’s mango and lime producing capitol.

What’s more, valley farmers insist that Manhattan will need the water in their precious reservoir for its processing operations. They worry mine runoff will contaminate the Piura River, which flows within metres of the TG-1 deposit. Many have also adopted an apolcalyptic acid rain scenario: the mine, they say, will generate a giant cloud of sulphide dust, which will dump toxic rain for 60 kilometres in every direction, rendering the region a moonscape.

Manhattan VP engineering Rick Allan rolls his eyes in frustration at the mention of such scenarios: “That’s silly. The only way you could get acid rain like that is if we used an archaic smelter system–and there will be no smelter here!”

The company plans to use a contained cyanide leaching system to process its gold, then a tank floatation system to isolate base metals. As for water, Allan says the company has its eye on the undeveloped Rio San Francisco, a different drainage 11 kilometres east of town, to meet its 110 litre/second needs. Manhattan’s only interest in the San Lorenzo system would be to improve it in order to provide dependable water for Tambo Grande town.

The company has tried to get its good news out. Soon after arriving, Manhattan opened a consultation office on the Plaza de Armas, where it screened mining documentaries and held public information sessions. It has also helped bring together a roundtable of NGOs charged with addressing social and environmental concerns. To combat the perceived conflict between mining and agriculture, Jorge Lanza, Manhattan’s general manager in Tambo Grande, flew community leaders to Chile’s Copiapo Valley, where healthy grape plantations sit within metres of copper mining operations.

“The people are learning from us what mining is about, and we are learning what their fears, expectations and worries are,” says Lanza, who has since left the company. “All the politicians, all the industrial leaders of this country and in this district are known for breaking their promises. So when we say we will protect the agriculture and environment, why should the locals believe us? It’s a problem of the general stereotype in Peru.”

Lanza was dismissed as this story went to press.

MAKIING ENEMIES

Manhattan has turned to the Catholic Church in its efforts to stem the tide of mistrust and aggression. But now even the clerics are growing impatient with the Canadians, says Alejandro Silva Reina, a board member of Diaconia, the church’s human rights wing: “We told the company, ‘We will work to build this bridge between you and the community. But you must promise to negotiate with them on an equal footing. That means providing information, being transparent.’ Well we are worried, because there is still no relationship. There is no bridge. That’s why we are seeing violence here.”

A survey Diaconia released in October 2000 outlines the depth of Manhattan’s challenges. Eighty percent of area residents still had a negative opinion about Manhattan’s presence. Two-thirds of people felt that the biggest problems facing Tambo Grande were mining and its side-effects. Most worrying, residents were completely divided on who should represent them in negotiations with the company. Only 10% chose the mayor’s office, while a third chose Ojeda’s hard-line Front (although another full third of residents had never even heard of the Front).

Silva says that if the company doesn’t find a way to get residents on side, the church will do whatever it takes to stop the mine–whether that means lobbying in Lima, at the World Bank or in Canada.

Considering that 87% of area residents lack regular, full-time work, and that nearly a third of farms have been repossessed since El Nino weather began to wreak havoc on agriculture in the 1990s, Manhattan has plenty to offer residents: Fifteen hundred short-term and 300 long-term jobs. Skills training, education and health programs. New homes for townspeople, some of whom now live in shacks constructed of mud and sticks. Paved streets. Twenty-four-hour water, where now taps run dry by mid-morning.

Manhattan is taking that message door-to-door to residents of Tambo Grande, rather than working through the mayor’s office or the politicized Front. It seems that after a year of confusion about who really represents the town’s interests, the company is cutting out the political middlemen. But the company has yet to focus its efforts on the hard line farmers of the San Lorenzo Valley. Manhattan simply won’t have concrete answers to their questions until it completes its EIA.

MISPLACED OPTIMISM

It’s been nearly two years since Manhattan’s agreement with the Peruvian government sent the company’s stock from C$2 to $8.50. Speculation was fueled by suggestions that the company would be acquired by a mining major hungry for new property, says Wendell Zerb, a mining analyst with Pacific International Securities in Vancouver. An impatient market has seen the stock slide back down around $2, but Manhattan remains one of the most optimistically capitalized exploration companies in Latin America, with about 34 million shares outstanding.

No wonder. Banter on Internet forums such as stockwatch.com suggests that investors are largely unaware of simmering tensions on the ground in Tambo Grande. And Carstensen’s drill crews keep turning up aces with their exploration work. First came another massive sulphide deposit, TG-3, less than a kilometre south of the deposits under the town. That discovery contains 110 million tonnes of ore containing copper, zinc, gold and silver. Then, last September, drilling 11 kilometres south of Tambo Grande revealed that a 53 metre-thick layer of sulphides might be Manhattan’s highest-grade discovery to date–capped with a gold zone similar to the one at TG-1.

The company is set to finish its EIA and feasibility study for development of the first pit this May–well ahead of schedule. Those studies should give investors certainty about the real economics of mining TG-1. Crucially, the report will also give Manhattan the tools it needs to educate residents about its plans.

With all the good news below ground, Andy Carstensen is a hard man to discourage as he surveys Tambo Grande. Told about the anti-Manhattan party in the Plaza de Armas the previous night, Carstensen is heartened. “Only 200 people?” he says, “That’s great. A year ago they would have pulled together a couple of thousand protesters. We’re winning the town over.”

His optimism is misplaced. Manhattan is running out of time in its bid to win friends in Peru. The bonfire demonstration was staged by only one of the region’s many anti-mining fronts. Weeks later, hundreds of townsfolk and farmers bussed to Lima to demand the government throw out Alberto Fujimori’s deal with Manhattan. Fujimori, the now-disgraced president who opened the door to Manhattan in 1999, was exiled in November under a cloud of alleged corruption. Peru will hold new elections in April, and Alejandro Toledo Manrique, the lead presidential candidate, has led a decidedly nationalistic, pro-agriculture campaign.

If the company can’t turn its good intentions into good relations, Andy Carstensen’s find of a lifetime may wait decades to see the light of day.